The associated model and definition that demonstrate a partial recreation of this project can be downloaded here.

South Park

Computational tools test the resilience of analogue rules for spatial partitioning within a small park.

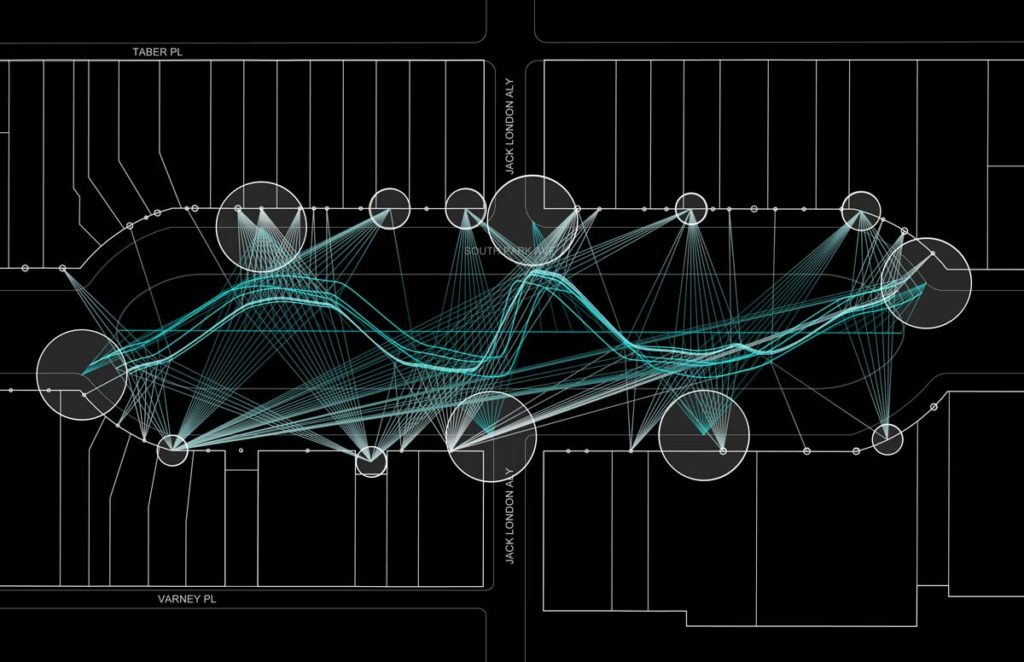

The design of the park utilises a ‘path finding’ tool which uses data collected on site to draw the path towards important areas.

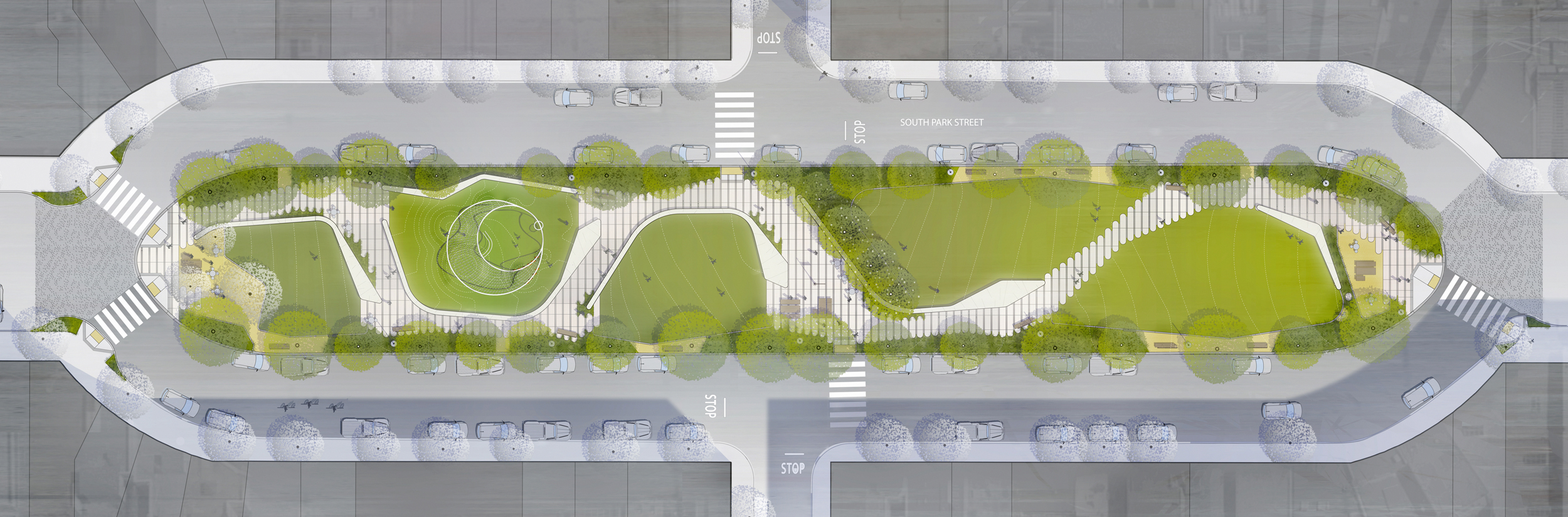

Image via Fletcher Studio’s project page (https://www.fletcher.studio/southpark)When Fletcher Studio first began work on San Francisco’s South Park, the initial design was developed “through iterative analogue diagramming”1 with a focus on “an intuitive understanding of the site and embedded in an analogue rule set.”2 This rule set was derived from on-the-ground observations, where the designers observed and collected data on “land use, park usage, circulation patterns, tree conditions and drainage systems”3 as well as “points of entry and desire lines.”4 This data was then aggregated into a “hierarchy of circulation patterns, access points, social nodes, existing trees and structures to retain”5 that worked to inform the width and position of the central path running through the park.

While the designers implemented a ‘rules based’ approach even from the earliest stages of site analysis, they also made of a point of “utilizing a combination of blend tools, manual adjustments, and hand drawings”6 which “allowed for idiosyncratic moments while conforming to a robust formal rule set based on environmental, spatial and material logic.”7

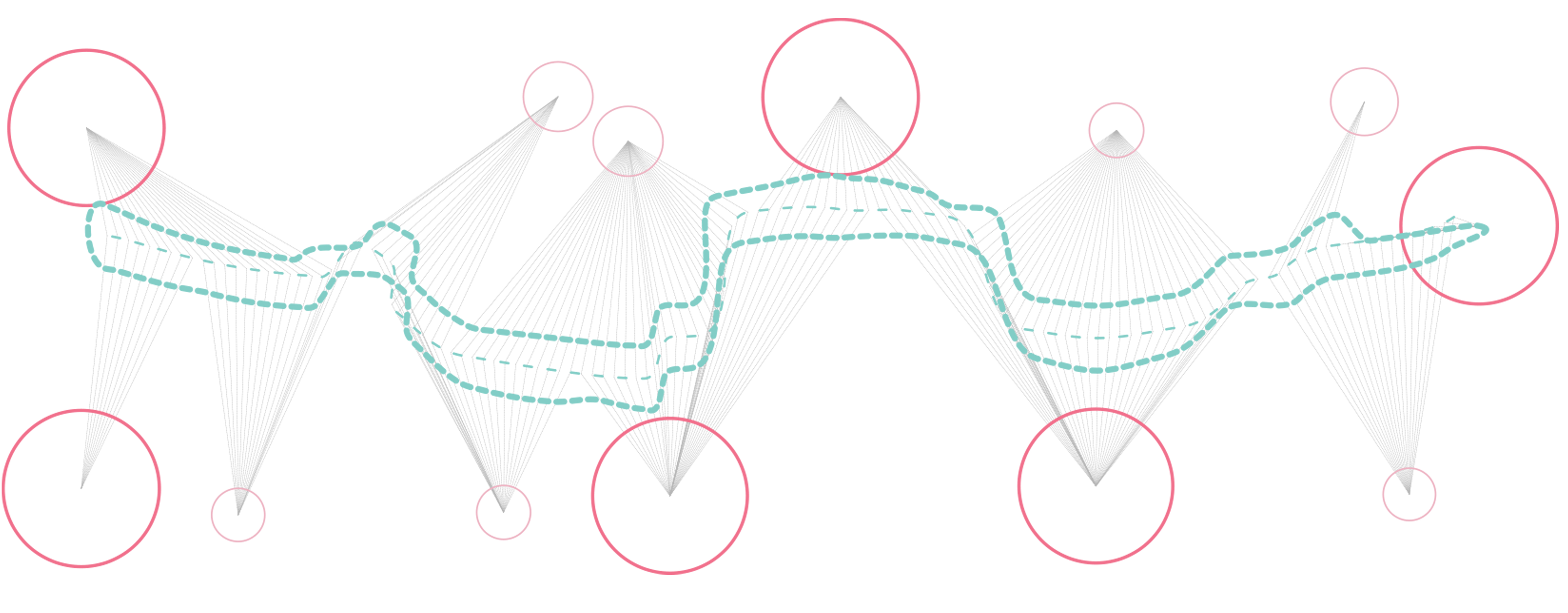

Control points of varying intensity are parametrised to manipulate the alignment of that path which runs through the site.

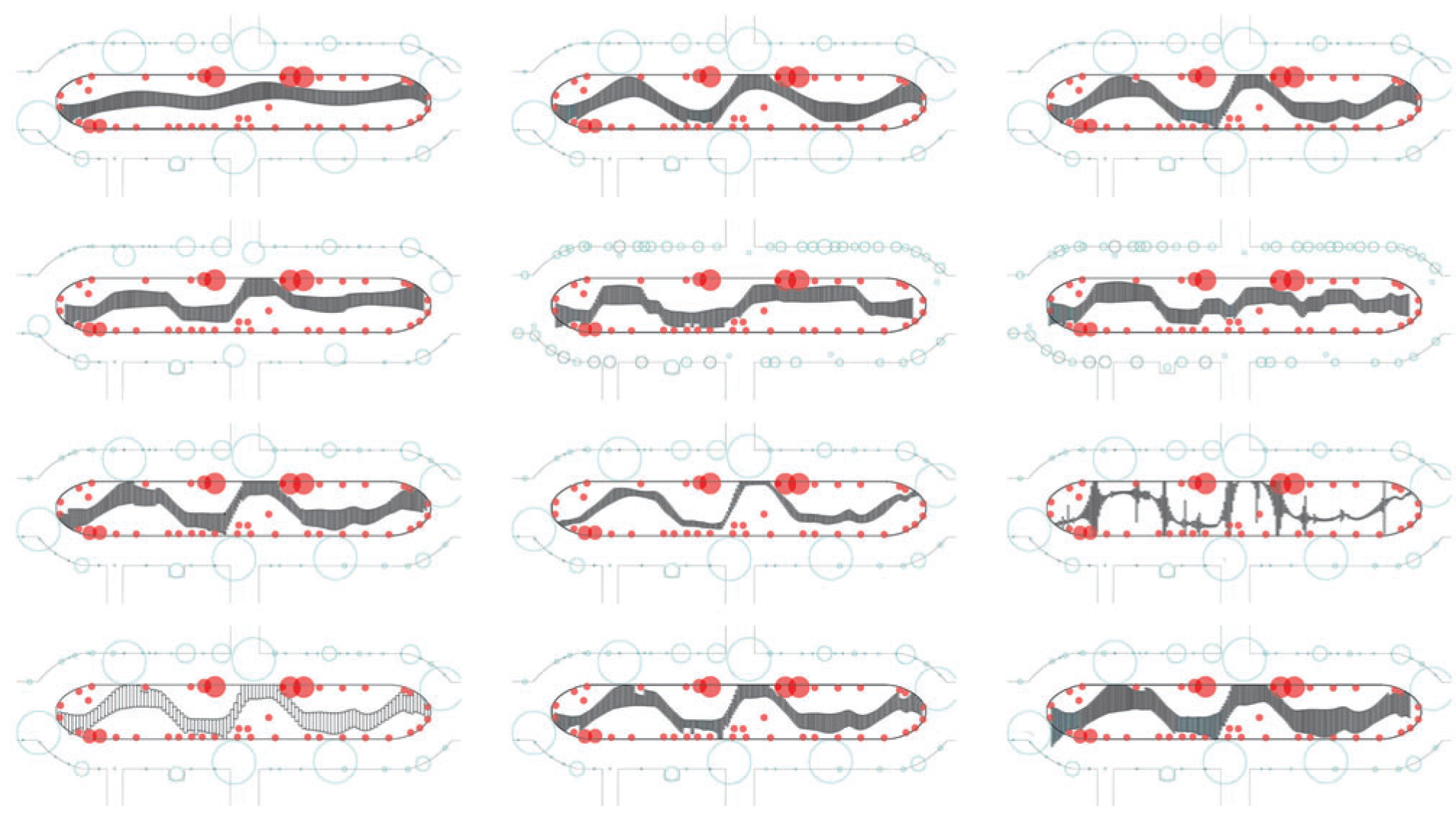

Fletcher Studio, image from Bentley, Chris, “Follow the Script”, Landscape Architecture Magazine 107, no. 7, 2016, p. 72Analogue rule sets are not — however — without problems of their own. Not only do they take a long time to test, but the very same ‘idiosyncratic moments’ that allow for the emergence of new and exciting design moves can also lead designers to overlook inconsistencies or failings in their logic. To address this, the system of organisation developed on paper was translated into a Grasshopper script and used to test “the design resiliency” of the diagrammed “tectonic and spatial systems.”8 This allowed the designers to iron-out any kinks in their logic while also iterating upon the design rapidly, and in detail, without violating the already-established constraints of their design concept.

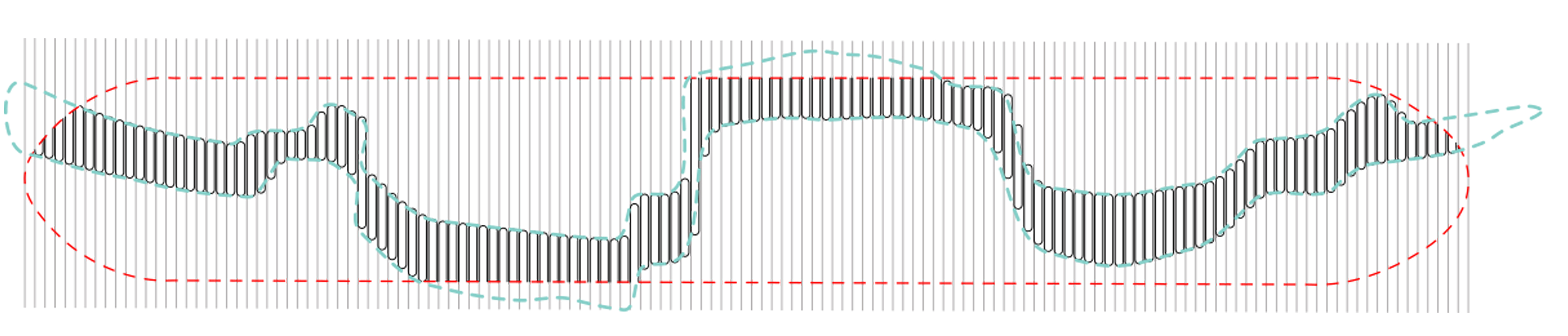

Parametric scripting allows for the rapid generation of highly detailed design iterations.

Fletcher Studio, image from David Fletcher, Parametric and Computational Design in Landscape Architecture, Bradley Cantrell & Adam Mekies (Routledge, 2018), p. 72By translating their rule set into grasshopper and refining it through iterative testing, Fletcher Studio eventually developed what they call a “live model”9 which:

“… was responsive, in the sense that various 3-D parameters could be modified and would universally update the entire model. Paving tablet width, length and distribution could be adjusted by modifying inputs, allowing the entry of exact values, or perhaps more intuitive site specific adjustments.”10

After the resilience of the initial analogue design parameters was tested, parametric design techniques went on to serve as a powerful aid for time-saving when working through the implications of design alterations in the latter stages of the design process. For example, “introducing a slight slope to improve drainage in one area… would create a problem in the site 200 feet away” and in being able to pinpoint this quickly, “the program helped them [the designers] juggle interdependent aspects of the design.”11

Parametric methods also presented significant benefits when it came to detailing and the associated rapid production of sheet files for engagement with stakeholders. The landscape architects noted that the Grasshopper definition had a powerful ability to work both in broad strokes and with minute detail simultaneously: “updates to wall profiles, thickness, edge radii and even the distribution and frequency of skate deterrents were automated.”12 This reduced the amount of time spent on slow and repetitive drawing, but also allowed the designers to produce detailed outputs — even complex full sheet file sets — much faster than would otherwise be possible.

While Fletcher Studio see the potential of computational tools, they are wary of these same tools becoming the be all and end all of a project. “Memory, experience, emotion and humour” writes David Fletcher — almost as a warning — “are not yet parameters that can be put into a parametric definition.”13

Reference Model

The reference model and definition for this project attempts to reverse-engineer the path finding rule-set developed for the South Park design. It also speculates on how parametric methods could have been used to help develop the lawn and garden-bed areas defined by the initial spatial allocation.

This first section of the script uses data from site to interpolate a line through the park pulled toward various data points according to their perceived importance. Here, for simplicity’s sake, the points are divided simply into 2 sets for ‘more important’ and ‘less important’ and are visualised with a set of larger and smaller circles. Thereafter:

- The initial ‘base line’ running through the centre of the park is divided up into points

- Vectors are created between these points and the centroid of the closest given number of data (attractor) points (circles)

- The points are then offset along this vector a given distance and the curve is then rebuilt

- This process is run twice, once with higher amplitude vectors for the ‘more important’ data points, and again with vectors of a smaller amplitude for the ‘less important’. The resultant line trends toward the various data points at differing levels of intensity

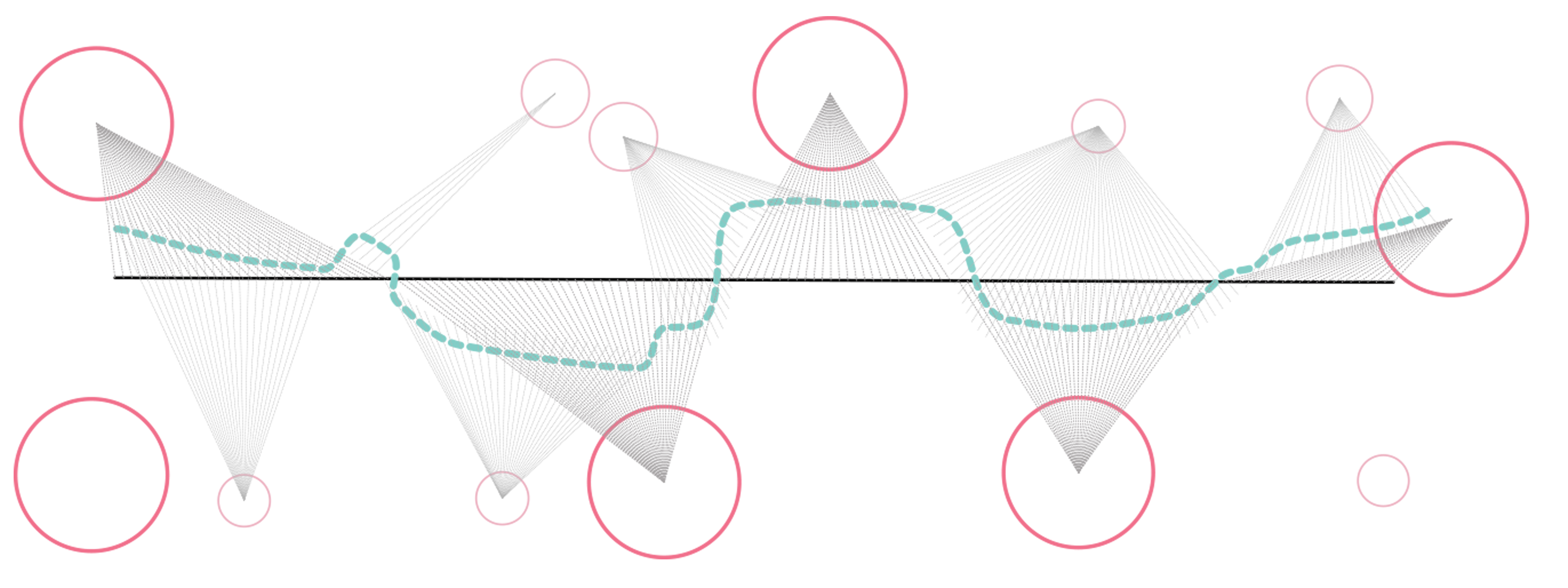

A straight base line is drawn toward control circles by vectors which warp and re-align it.

Albert Rex, for groundhog.philipbelesky.comThis second step generates offsets from the initial line to define the width of the path. These offsets are also influenced by the same input data or ‘attractor points’ discussed earlier. However, this iteration only includes the attractor points on 1 side of the park so that one line is offset in one direction and another in the opposite. As a result, the path grows wider when it is closer to more powerful attractor points — doubly so when points are present on both sides.

A path is offset out from the initial line. Offset distances also dependant on control points.

Albert Rex, for groundhog.philipbelesky.comAfter the boundaries of the path are defined, the lines generated in the previous steps are used to produce a detailed paving system that responds to changes in data input. While straight lines are lofted off the initial base line, the 2 offset lines generated in step 2 are used as cutters to fit these lines to the curve of the path. These lines are then offset, capped, and filleted to replicate the shape of the pavers in the original design. Parameters are defined to control the paver’s width and spacing before they are trimmed them to the outer boundary of the park.

A grid allows for the introduction of paving over the designated path area. A site boundary curve clips this paving to stay within site.

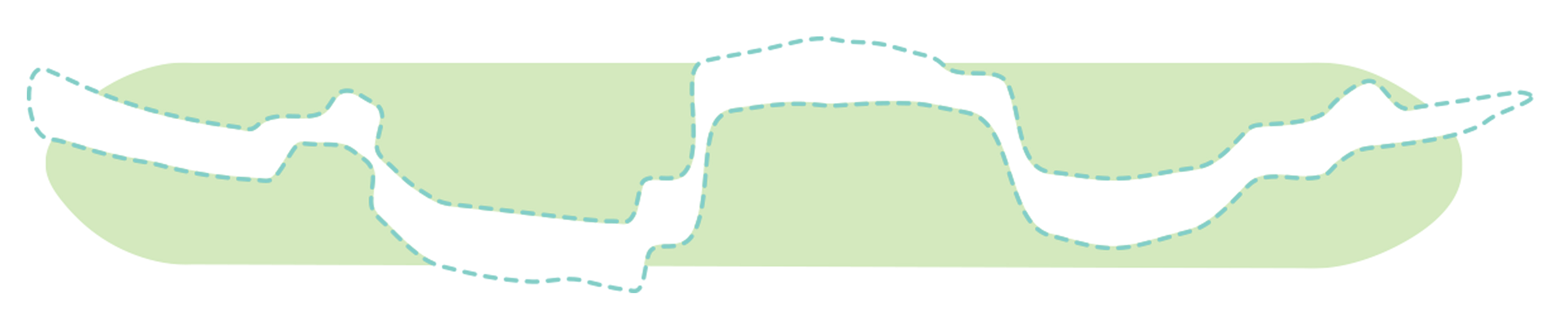

Albert Rex, for groundhog.philipbelesky.comThe shape of the paved area of the park can then be subtracted from the total site perimeter to define the area that can be given over to garden beds and lawns.

Area not taken up by the path is identified.

Albert Rex, for groundhog.philipbelesky.comThe size and shape of garden beds is also determined by the initial input data set: the attractor points of this definition. The beds are generated by offsetting the straight segments of the park boundary along the inverse of the vectors used to define the initial path boundaries.

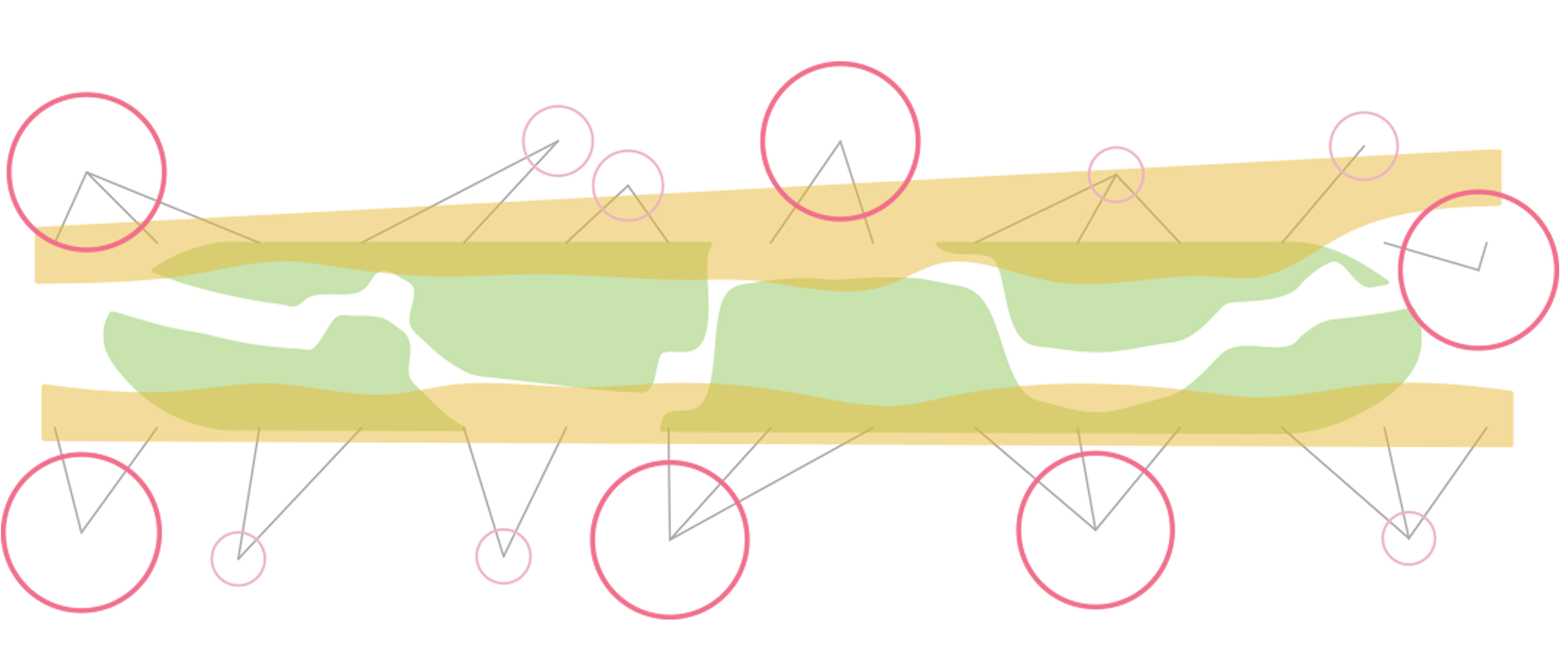

Boundary offsets introduced to divide lawns and garden beds. Lawns: Green. Garden Beds: Green yellow overlap.

Albert Rex, for groundhog.philipbelesky.comOnce defined, the planting of the lawn and garden bed could also be controlled parametrically using a planting mix spreadsheet and a series of Groundhog components.

Boundary offsets introduced to divide lawns and garden beds. Lawns: Green. Garden Beds: Green yellow overlap.

Albert Rex, for groundhog.philipbelesky.com

The script generates a path, garden beds and lawns, all based on site boundaries and usage data recorded on site

Albert Rex, for groundhog.philipbelesky.comWhile South Park is a small site, the capabilities of the parametric methods used in its design also have clear implications for larger-scale design scenarios. “In response to the observed resiliency of the rule set” writes David Fletcher, “we foresee application of this system to large scale linear open spaces…Potential sites for this application include: urban waterways, waterfronts, corridors, linear open spaces and right of ways.”14 As the general logic of the script is agnostic to site-specifics, it could be applied to define a path running along a coastline. This path could then continuously shift its form according to a series of strategic attractors that might add extra span according to adjacent amenities or areas of higher pedestrian traffic. The ability to quickly iterate upon a design by tweaking a small set of parameters becomes more powerful at these larger scales, where it is more difficult to develop a comprehensive understanding of an entire landscape.

The script still operates when site boundary and path are altered. From this we can infer that it is based on a relatively ‘resilient’ rule set.

Albert Rex, for groundhog.philipbelesky.com

The script is capable of operating over a wide range of environments. Here it regulates how a path moves through a forest.

Albert Rex, for groundhog.philipbelesky.com

The script can be easily altered to accommodate additional, site-specific. variations. Here an additional path is influenced by the original set of attractor curves and cuts under the first path, while at the same time the definition rebuilds garden beds around it.

Albert Rex, for groundhog.philipbelesky.com

Grasshopper definition recreating the basic path distortion effect.

-

David Fletcher, “The Parametric Park,” in Codify: Parametric and Computational Design in Landscape Architecture (London, United Kingdom: Routledge, 2018), 72.↩

-

Fletcher, “The Parametric Park,” 72.↩

-

Fletcher, “The Parametric Park,” 72.↩

-

Fletcher, “The Parametric Park,” 72.↩

-

Fletcher, “The Parametric Park,” 72.↩

-

Fletcher, “The Parametric Park,” 72.↩

-

Fletcher, “The Parametric Park,” 72.↩

-

Fletcher, “The Parametric Park,” 73.↩

-

David Fletcher, “South Park: San Francisco’s Oldest Park Reinvented,” Landscape Middle East, 2018, 39.↩

-

Fletcher, “South Park,” 39.↩

-

Chris Bentley, “Follow the Script,” Landscape Architecture Magazine, 2016, 68.↩

-

Bentley, “Follow the Script,” 68.↩

-

Fletcher, “The Parametric Park.”↩

-

Fletcher, “The Parametric Park,” 75.↩